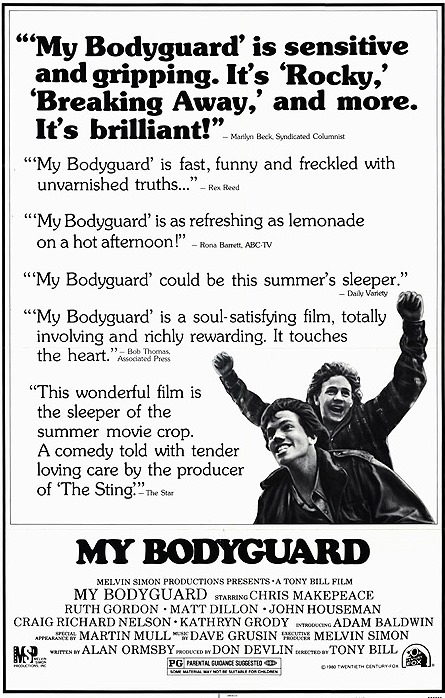

A wistful look at this poignant slice of 1980 life

“Ricky Linderman”. It’s a name that has stayed with me. He’s the tragic strong, silent figure in the middle of the action of 1980’s My Bodyguard. As a child of 12 seeing this film during a free trial of HBO in 1981, he was the type of character that I wished I had around as my bodyguard.

I can’t speak for how kids have it today, but I am aware of a movement to bring attention to the injustice of bullying. Whether or not children are more protected as a result of the outcry, I cannot say. Nor can I claim that it’s a good thing if they are provided with “safe spaces” that pamper them. I can only speak from my experiences. And entering seventh grade in 1980 was a challenge for many of us. It was the days when everyone took a bus or walked to school. If one of our parents thought they’d wait with us at the bus stop, or drop us off at the front of school, they were mistaken. There was nothing worse than having classmates witness you being coddled. It was a sure-fire invitation to be teased. Such taunting could escalate depending on who made it their cause – there were some pretty damn malicious kids. As a result of it all, independence was instilled early. We roamed free, naïve to any threats besides bullies. And we liked it.

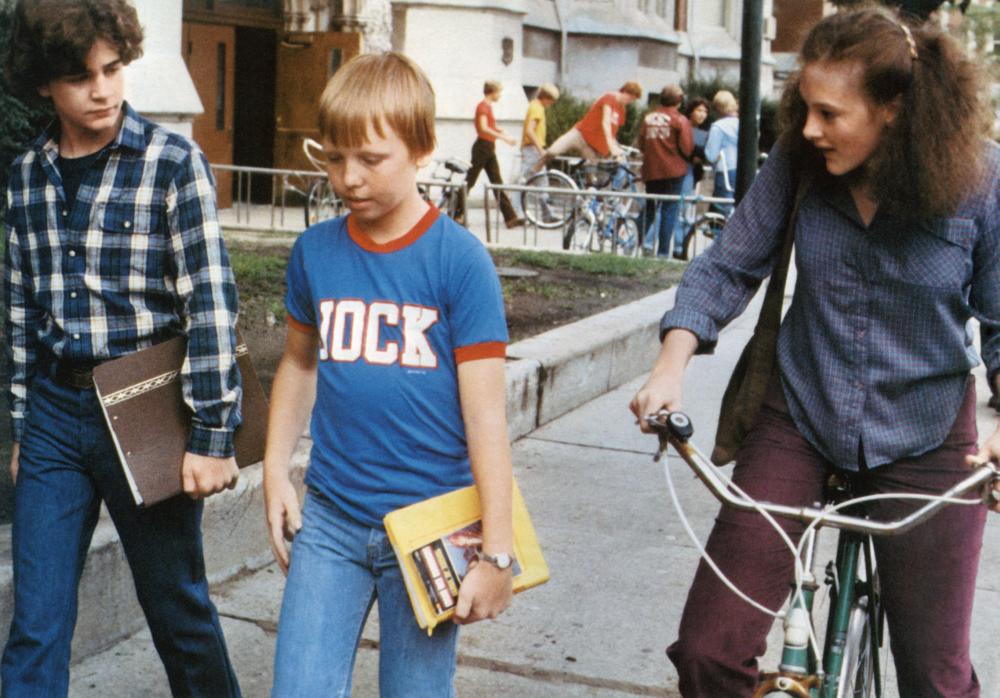

In the film, nerdy Clifford Peache, played by Chris Makepeace (shortly after his huge hit with the Bill Murray comedy Meatballs), moves into a luxury Chicago hotel managed by his ever-busy father (Martin Mull). Potentially threatening his dad’s job are the wild antics of his hard drinking over-sexed grandmother, who has a habit of hitting on the older men in the hotel bar. Similar to the live-to-the-fullest attitude of her part in 1971’s Harold and Maude, Ruth Gordon plays the role with a brazen quality that is unexpectedly offset by deep intuition and sympathy.

Clifford learns that his new Southside school is rougher than what he’s been used to. A group of bullies extorts lunch money from defenseless students under the guise of taking it for “protection”. The gang is led by a tough punk named Moody, convincingly portrayed by pretty-boy-of-the-day Matt Dillon (who went on to have a successful career). Though most of the victims know they are paying essentially just to be left alone, there is a figure in school they believe does pose a threat to their safety – Ricky Linderman (Adam Baldwin in his first role), a dirty faced fully grown young teen that allegedly killed a kid and raped a teacher. Mysterious and brooding, even Moody’s gang stays out of his way – a fact that is not lost on Clifford.

After much dogging, a reluctant Linderman eventually agrees to be employed as Clifford’s bodyguard. They develop a genuine friendship, and Cliff learns that Ricky’s overblown stigma is based solely on the fact that his younger brother accidentally shot himself and Ricky was the first to find the body. The subsequent gossip spawned the urban legends surrounding his reputation.

Clifford accompanies Ricky on junkyard quests for a holy-grail missing piston needed to complete a vintage motorcycle re-build project. When Clifford naively finds it on one such trip, a feel-good 80’s moment of slow-motion victory ensues, followed by a classic extended montage of the pair joyriding through the mean streets of Chicago (try doing that today).

After witnessing the brutal bullying of Moody and co. earlier, a highlight of the film comes when a bit of sweet justice is served. I found myself yelling “YES! TAKE THAT!” after Linderman is publicly confirmed as the new bodyguard at the expense of Moody’s humiliation. Cliff and his friends enjoy newfound security. Their core group now includes a red-headed foul mouthed kid who appears late to puberty, Ricky, Cliff, and Shelly, a 13-year-old with braces (played by an impossibly young Joan Cusack).

It’s interesting to note the dynamic of the friendships minus cell phones and social media. Despite their absence, there were things that connected us all. For instance, the majority of adolescent boys in 1980 loved Star Wars. And sure enough there are traces of it throughout My Bodyguard. Being a member of that generation, my eye is trained to spot them – an X-Wing model in the father’s office, a TIE Fighter model and an R2D2 & C3PO poster in Clifford’s room (blink and miss ‘em!). Commonalities were simpler and necessary. “You like football? Cars? Music? Let’s be friends”. Unlike today, when everything is divided into countless sub-genres from pop to politics; young lives have become needlessly complicated.

Enjoying the fresh air of freedom, Cliff & co hang out in a park only to learn Moody hired his own bodyguard – a guy that brings to mind Vin Diesel of twenty years later. He gets in Ricky’s face for an extended bout of what I can only describe as authentic bullying. The abuse is so well-acted it brings me back to being that kid on the receiving end. It’s unsettling, and you’re left rooting for Ricky to fight back. But in the movies most disheartening moment, he doesn’t. Moody wheels the beloved bike into a lake, and a defeated Linderman abandons his friends.

Enjoying the fresh air of freedom, Cliff & co hang out in a park only to learn Moody hired his own bodyguard – a guy that brings to mind Vin Diesel of twenty years later. He gets in Ricky’s face for an extended bout of what I can only describe as authentic bullying. The abuse is so well-acted it brings me back to being that kid on the receiving end. It’s unsettling, and you’re left rooting for Ricky to fight back. But in the movies most disheartening moment, he doesn’t. Moody wheels the beloved bike into a lake, and a defeated Linderman abandons his friends.

As an involved viewer I was truly pissed that Ricky didn’t retaliate. I already reached my own breaking point and flailed my fists in the air! Clifford doesn’t give up on his friend, though, and learns the truth behind Linderman’s refusal to strike back. Another confrontation soon ensues in a thoroughly convincing fist fight between Ricky and “Vin Diesel”. It plays out just like brawls I used to witness in my youth – another achievement of authenticity. It gets a little outrageous when Clifford jumps in and takes on Moody, but it’s all in good fun.

I’m fairly certain every school had its own version of Moody and his cronies. ‘Cool’ kids who kept their peers fearful. They genuinely could make lives miserable, it was no joke. Despite the behavior, you didn’t have to worry about getting stabbed or shot. In those days, parents encouraged their kids to fight back. That’s how you earned respect. You took your lumps, learned from it and moved on. But the potential consequences aren’t nearly what they are now. Safety – another reason for nostalgia?

Another indication of how different things are is an act portrayed as kid stuff that is downright criminal today. On the balcony of their suite, Ricky has a telescope set up to watch “heavenly bodies” – unsuspecting women in their city apartments. He even knows their schedules and has given them names. Adding to the creepiness, his father joins in, claiming he “needs it more”. As repulsive as it sounds, it plays out like good clean fun. And unless you were a kid back then, there’s no way to explain that’s all it really was.

My Bodyguard did well at the box office and on home video but it has been all but forgotten. From the film’s string-heavy music score to the attire of the cast, it’s a wildly fun time capsule. Older audiences will recognize appearances by Cheers’ George Wendt (“Norm!”) and stuffy Englishman John Houseman, the aged character actor known in 1980 for a series of Smith Barney commercials and his catchphrase “we make money the old fashioned way, we EARN it”.

There’s no question that My Bodyguard earned its audience. It’s got the charm and laughs of a good comedy, but most of all it has heart. It is not a timeless film, stuck forever in 1980, but it is pure. Were it to be remade, there would almost certainly be Gay overtones, outright or implied (not that there’s anything wrong with that!), and other elements forced for the sake of current sensibilities. I am curious how modern filmmakers would respond to this well-meaning gem. Would some ridiculous unintended subtext be interpreted? Abused by the modern bullies of cynicism and entitlement, nearly lost forever is the light-hearted sincerity of a generation that made such a film possible. And maybe THAT’s worth sticking up for.